As a girl, Gloria Steinem’s life was filled with cross-country travel, a search for adventure, and exposure to the lives of all types of people across the United States. Now, as an adult and a world-renowned activist, Steinem recounts how her life of travel, conversations with strangers, and desire for change led to a life of activism and leadership. Along with her own growth, Steinem details the growth of a movement for equality that’s still being fought today.

I admit I didn’t know much about Gloria Steinem before picking up My Life on the Road. I knew her name was synonymous with the 70s feminist movement and women’s rights advocacy, but that was pretty much where my knowledge ended. After finishing her latest novel, my impression is: Gloria Steinem was—and, at the age of 82, still is—a force to be reckoned with.

I admit I didn’t know much about Gloria Steinem before picking up My Life on the Road. I knew her name was synonymous with the 70s feminist movement and women’s rights advocacy, but that was pretty much where my knowledge ended. After finishing her latest novel, my impression is: Gloria Steinem was—and, at the age of 82, still is—a force to be reckoned with.

My Life on the Road is a retelling of Steinem’s life of activism, a story that she weaves using the motif of travel. In this book she acknowledges the influence that her nomadic childhood had on the rest of her life; her father was a larger-than-life character who refused to put down roots anywhere, packing his family up often and moving across the United States. Steinem found herself mimicking this restless wandering, despite yearning for a solid home as a child. But she credits her father for instilling the love of travel in her, which allowed her to lead the proactive life she has led.

Steinem’s life of travel is so extensive that it seems almost unbelievable at times. Never settling in one place allowed Steinem to organize the National Women’s Conference in 1977, ride in a cab with (and be insulted by) Saul Bellows, witness Martin Luther King Jr’s famous speech first-hand, and wave goodbye to John F. Kennedy the day before he was shot.

Steinem did not fight solely for feminism, as I had previously thought, but for equality across genders, races, sexualities, etc. Her writing is insightful and challenging. She offers alternate ways of looking at well-worn social issues, making them still topical in 2016 despite being cultivated in the 1970s. For example, her meditations on the lack of diverse representation in women’s rights are what we call “intersectional feminism” today. Steinem encourages everyone—male and female—to travel as much as they can, to experience the world for what it is and not for how it’s presented in the media. After all, being in new places and meeting new people breaks the “supposedly enlightened idea that there are two sides to every question. In fact, many questions have three or seven or a dozen sides.”

_______________________________________________

Share your thoughts in the comments! Some questions to consider are:

1. Steinem writes “[The road] leads us out of denial and into reality, out of theory and into practice, out of caution and into action, out of statistics and into stories…” Have you ever been on a trip that changed the way you saw something? Has an experience with travel ever opened your eyes to something new?

2. “Perhaps our need to escape into media is a misplaced desire for the journey.” Do you think this is true? Have you ever used a book, movie, television show, etc. to satisfy a craving for travel and experience?

3. Steinem is of the opinion that meeting in person always trumps gatherings on the Internet. In an increasingly digital world, is her dismissal of the Internet’s power fair? Or do you think it should be given more credit for its ability to bring people together?

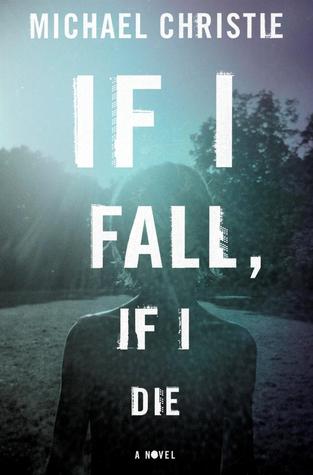

Thunder Bay is a long, long way from southern Ontario. Almost 1000 km sit between it and Toronto, and the difference between the two is something author Michael Christie is very familiar with. Christie was born and raised in Thunder Bay, and his portrait of it always feels entirely authentic, if quite unflattering. The city is not the focal point of

Thunder Bay is a long, long way from southern Ontario. Almost 1000 km sit between it and Toronto, and the difference between the two is something author Michael Christie is very familiar with. Christie was born and raised in Thunder Bay, and his portrait of it always feels entirely authentic, if quite unflattering. The city is not the focal point of