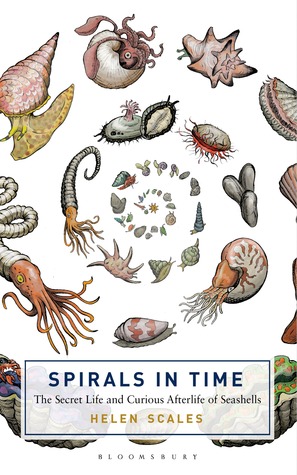

If you’ve ever picked up a seashell and wondered how those shells came to be – what created the seashells that she sells by the seashore? – then Spirals in Time by Helen Scales is the book for you!

If you’ve ever picked up a seashell and wondered how those shells came to be – what created the seashells that she sells by the seashore? – then Spirals in Time by Helen Scales is the book for you!

Starting off with delightful endpapers, Scales takes you through the varied and multitudinous creatures that inhabit these shells and build their homes one layer at a time over time: molluscs. The Mollusca phylum is constituted of invertebrates that live in water… except when they don’t. It’s complicated. To begin with, it’s pretty complicated to even define what constitutes a mollusc when we move away from looking at genetic similarities and onto physical ones. They’re all invertebrates, for one. Although some of them have a cuttlebone, it’s not strictly speaking a vertebrae, so they do all fall under the category. They’re also all… squishy (that’s a technical term*)? What about shells? We’ve been talking about shells! I’m sure it comes as no surprise that although seashells are all made by molluscs, not all molluscs make or make use of shells. Scales sums it up in the first chapter: “Having a soft body and a hard hat is not enough for an animal to be considered a mollusc” (p.26), and “the core concept of what it means to be a mollusc remains deeply contentious” (p.28). This coming from someone who studies them for a living**, or at least wrote an entire book on them.

For all their mysterious origins and shared characteristics (how does one make it into the Mollusca group?), these creatures follow what appear to be rather logical rules in how to build their shells. Indeed, a famous image that you have more like than not have seen is one of the logarithmic spiral that becomes visible after you cut a nautilus shell in half. (The logarithmic spiral is found across the world, and not just in nautiluses.) Scales describes how molluscs (might) make their shells, because for all their diversity of patterns, the process of seashell creation stays remarkably constant throughout the phylum. She also covers the effects of ocean acidification on molluscs that rely on calcium-carbonate shells, as this directly affects how much energy it takes for these organisms to create their homes, leaving less time and energy for food, rest, and sex.

Spirals in Time is remarkably informative and well organized, incorporating anecdotes into what could otherwise present as information-heavy, and if you really only want to read one book on molluscs, this would probably be it.

Interested in more molluscs? Follow me under the cut!

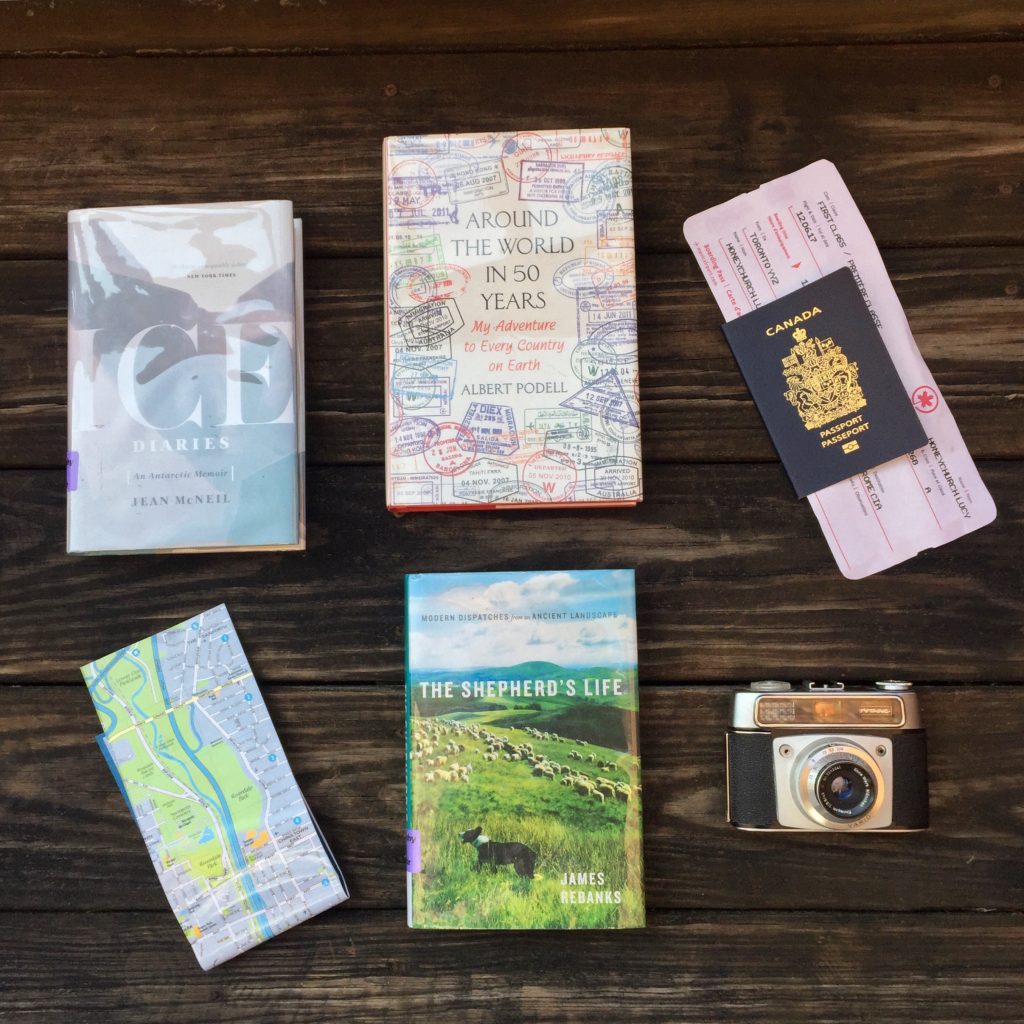

Travel the world from the comfort of your own home, no passport required.

Travel the world from the comfort of your own home, no passport required.