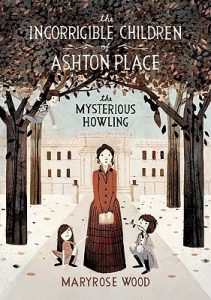

I don’t think I’ve ever consumed an entire series as quickly as I did this one: The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place. (The Chronicles of Narnia are a very close second, because I inhaled those as well, though in light of a recent rereading, I would have to put the Incorrigibles at the top.*) To be perfectly honest, I only learned of it and picked it up because they’re illustrated by none other than Jon Klassen, but I’m so glad I did!

I don’t think I’ve ever consumed an entire series as quickly as I did this one: The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place. (The Chronicles of Narnia are a very close second, because I inhaled those as well, though in light of a recent rereading, I would have to put the Incorrigibles at the top.*) To be perfectly honest, I only learned of it and picked it up because they’re illustrated by none other than Jon Klassen, but I’m so glad I did!

The series is a delightfully written mystery that will keep you making connections between all the little details Wood drops left and right at every turn, whether it be the mysterious howling on Ashton grounds or the oddly coincidental wolf theme popping up at the bequest of a certain…. A.? Wood keeps you guessing with every book at how things are connected: was it really just a chance ad in the papers that got Penelope Lumley working for the Ashtons? Were the Incorrigibles actually raised by wolves? And what’s with Old Timothy? Just whence does Penelope Lumley’s seemingly infinite pluck come?

I won’t go too much into detail because I don’t want to spoil it for you, but Wood definitely keeps you on your toes and grabbing for the next installment. I personally quite enjoyed the asides, along with the fast pace and wit, but where I think Wood really excels is where this series has something to appeal to a variety of age groups. (The last book in the series, The Long-Lost Home, is set for release next June, and we’ve placed it on order, so beat the lines and put yourself on the waiting list now!)