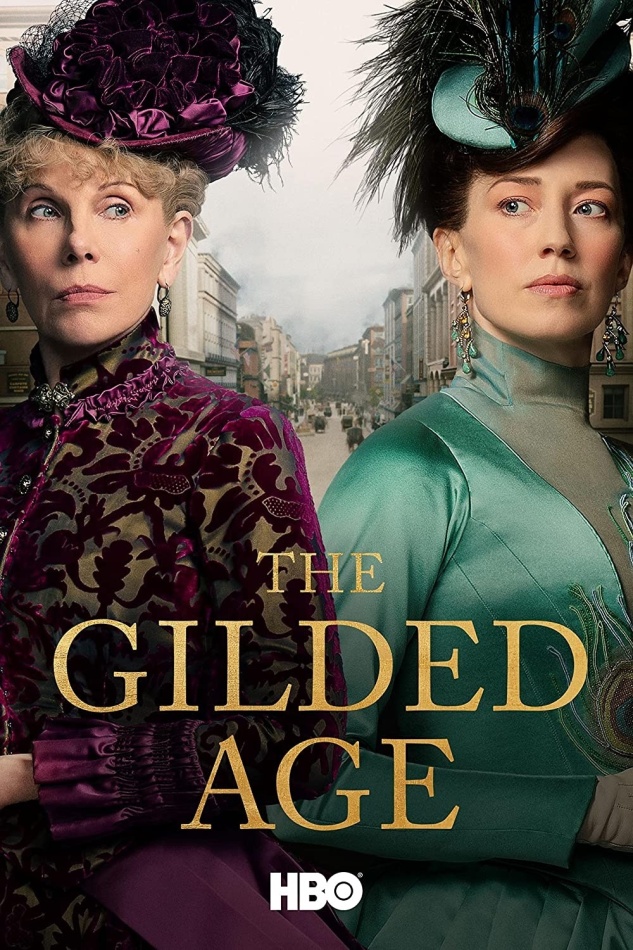

Lately the only thing I’ve been wanting to watch during my downtime is period dramas. Something about the coziness of low-stakes drama fits with the coziness of the holiday season. I burned through Hotel Portofino on PBS Masterpiece; I dipped my toe into Apple TV’s (largely silly and CW-like) adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Buccaneers. But the one that has really captured my attention is HBO’s The Gilded Age, whose second season is now airing.

Created by the same guy that did Downton Abbey, The Gilded Age follows a similar upstairs-downstairs approach but moves the focus across the pond to 1880s New York. The drama follows Old New York society—big money, bigger dresses—as they are infiltrated by the audacious new money Russell family (based on the real-life Vanderbilts). Mrs. Russell is a scheming queen whose only goal is to secure a spot at the coveted Academy of Music opera house (and to marry her daughter off to the richest, most impressive man she can find). Mr. Russell is a robber baron, a ruthless railroad tycoon who will extort anyone and everyone in order to support his wife’s ambitions. Truly, they are the power couple to end all power couples. The drama, in comparison to other shows, is very low stakes and ridiculous (one of the climaxes concerns a character walking dramatically across the street), which is appropriate for a show whose namesake, coined by satirist Mark Twain, denotes a “period of gross materialism and blatant political corruption.” Edith Wharton’s famous Gilded Age-era novel The Age of Innocence is full of contempt for the Old New York families and their highly rigid, Anglophilic society (“gilded”, of course, refers to the thin sheet of gold that hides less glamorous material). Still, it makes for engrossing television!

The show’s second season delves into more serious subject matter by tackling the plight of railway workers and their long fight towards unionization. After years of being subjected to horrendous (and dangerous) working conditions, the railway men take up the chant “Eight! Eight! Eight!” as they demand an eight-hour workday, eight hours for sleep, and eight hours of recreational time. It’s fascinating to watch the structure of our own modern lives be wrestled into shape by the hands of these working class men—a structure that has somewhat broken down in our technological age (how many of us take work home, or stay in the office past the allotted eight hours?), but one that we have been lucky to benefit from. (Jenny Odell’s insightful How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy discusses the formation of 19th century unions as an early form of protection against soul (and body) crushing capitalism). These workers placed themselves in the literal line of fire to advocate for change.

Continue reading